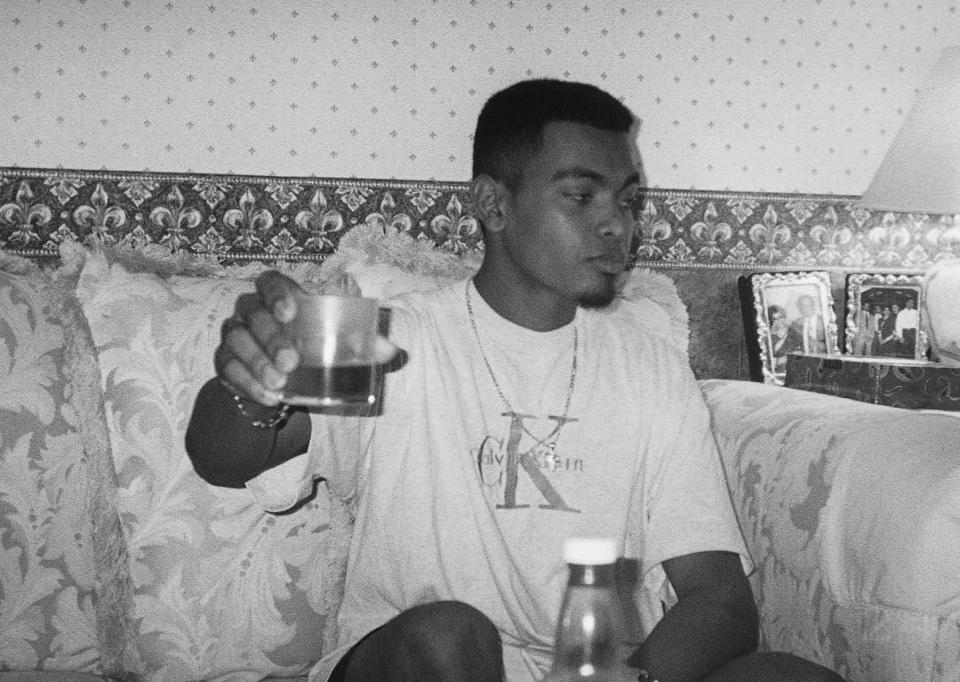

VICTORIA Cross hero Johnson Beharry reveals he once ran a drugs gang and carried a sub-machine gun for protection.

Johnson — the first soldier in 18 years to win Britain’s highest honour — was the kingpin of a knife-carrying gang that oversaw £70,000-a-time cocaine deals.

But the dad-of-two, 38, who received his honour from the Queen for bravery heroics in Iraq in 2004, quit the murky role for the military.

He says: “The Army saved my life. I would have ended up dead or in prison.”

Now, as knife-crime deaths soar to a record high of 35 in London this year alone, Johnson says he is using his inspirational story to help drag others out of violent crime.

He is also calling for the Government to educate kids as young as NINE about the pitfalls of gangs, adding: “Telling them at 15 is too late. You may have lost them by then.”

Lance Sergeant Johnson, who is serving with the 1st Battalion Princess of Wales’s Royal Regiment, tells The Sun on Sunday: “I’m lucky that I have the VC letters next to my name when it easily could have been RIP.

“When I was in the gang, we used to carry knives or guns for protection. We were scared of people coming to get us more than police catching us.

“The Army rescued me from that life. Two of my friends are dead and two are doing long prison stretches.

“Hopefully, I can help save others from gangs. I’m proof you can turn your life around.”

Through his JBVC Foundation, Johnson is helping young offenders stay off the streets.

In an exclusive interview, he reveals how he went from dealing small amounts of marijuana to running a Class A drugs racket within 12 months, almost got caught with his gun by the police and how the gang cut ties with him.

Today, he is also calling for more youth clubs and for teachers to better identify gang-related behaviour before kids get sucked into criminality.

He says: “We are failing our kids. The Government is spending money on the wrong things. It needs to get to the root of the problems before it gets out of control and kids end up in young offenders’ institutes.”

Met Police records show 37,443 recorded knife offences and 6,694 recorded gun offences across the UK in the year up to September 2017. Four teenagers were stabbed to death in London on New Year’s Eve alone, and 22 killed in March — meaning the capital has a higher murder rate than New York, which has 21.

Johnson was 19 when he came to live in Heathrow, West London, from Grenada in 1999. He says: “We didn’t have much. When I came to the UK to live with my aunt I started working as a painter and decorator.

“I was earning lots and would go out partying, drinking and smoking weed. That’s how I fell into a gang, it provided a family-like base.

“I had a bit of cash so, initially, I’d buy £300 of marijuana and deal it on a small level.

“Then it was £1,000-worth and then it became a business. I got introduced to people who could sort large quantities of cocaine and speed. It spiralled out of control.”

Within months, Johnson was leading a gang of ten based in Harlesden, North West London, which would deal drugs as far as Southampton.

He says: “No one in my family or at work knew I was involved in it. We were spending £70,000 for one shipment of drugs and dealing it.

“I carried an Uzi in the boot of my black Peugeot 205 for protection, although I never had to use it.

“In 2000, I was driving through Peckham, in South London, and got pulled over by a policeman.

“He said: ‘Do you know why I stopped you?’ My heart was pounding because my Uzi was in the boot but he said my tax disc was out of date. I managed to talk my way out of it.” But in early 2001, Johnson had a “light bulb moment” which changed the course of his life for ever.

He says: “My grandma called and told me she needed money. I had loads of it but it was dirty cash.

“I thought, ‘What would she think of me?’ I made the decision to stop. I felt ashamed and was at an all time low. I had to get out.

“I told the gang I was out and that I’d seen an advert for the Army.

“They did everything to make me stay and told me the Army was racist, but my mind was made up.”

Johnson was rejected by the Army THREE times after he told them of his gang history — but on the fourth attempt later that year he finally got in. He says: “I left one gang for another. Except the Army is a proper family.

“I never missed the gang once. I tried to stay in contact with them but they didn’t want to know.”

Johnson says he had a shock when he received his first military weekly payslip of just £40, an amount he “could earn in about ten minutes in the gang”.

He says: “Money on the street is easy and comes quick but, eventually, you will always get caught. I had to readjust my mind to living the straight life.”

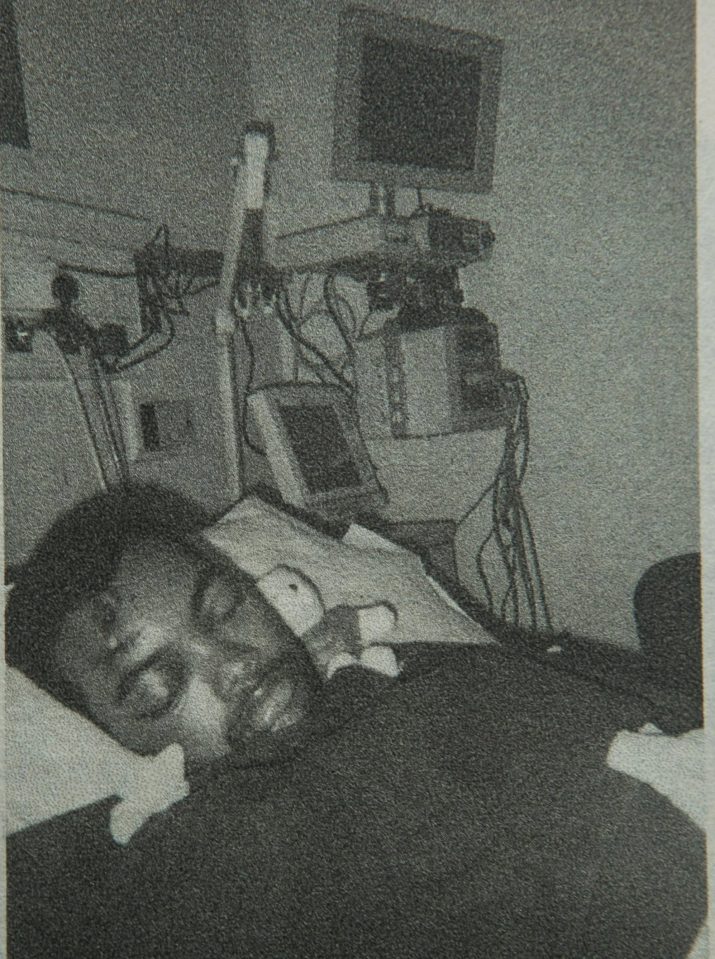

Johnson — when just 24 — went on to win the Victoria Cross for two acts of heroism at Al-Amarah, Iraq, in 2004 when he saved around 30 comrades.

Four years later, people he used to know from his gang days were arrested as police smashed a £100million cocaine empire. Only one person he knew from those days — a friend who is working for a council — is now living a normal life.

In 2014, Johnson — who lost 40 per cent of his brain in the Iraq attacks — set up the JBVC Foundation.

It has just finished its biggest project yet — helping to keep 20 young people aged 15 to 25 off the streets after they have served their time. Their sentences range from a few years for drug dealing to ten years for manslaughter.

He says: “We see young gang members in prisons three months before they are released. We try to give them direction, sort their CVs out, some form of ID, get them job placements, give them support.

“We’ve managed to get one kid a trial at QPR, another job at a printing company. Only two of the 20 have gone back to the gangs and reoffended — giving them a 90 per cent rehabilitation rate.”

Johnson thinks the number of knife and gun offences is higher than numbers reported, saying: “Our case workers get mothers telling them their son has been stabbed and they never get reported, all the time.

MOST READ IN NEWS

“People say the police need to stay on top of the problem but the change has to start with the Government. We need to talk to kids at a young age so they don’t get into gangs.”

But Johnson, who lives in East London with his four-year-old son Ayden and wife Malissa, says his biggest fear is his son going into gangs.

He says: “I worry about it so much that I think I may move out of London.

“Hopefully I can show him, like I can show other kids, that gangs are not the way to go and that you can always turn your life around.”

- To find out more about the JBVC Foundation’s work, see .

GOT a story? RING on 0207 782 4104 or WHATSAPP on 07423720250 or EMAIL exclusive@the-sun.co.uk