I discovered I was intersex when I was 38 but I’m no longer ashamed

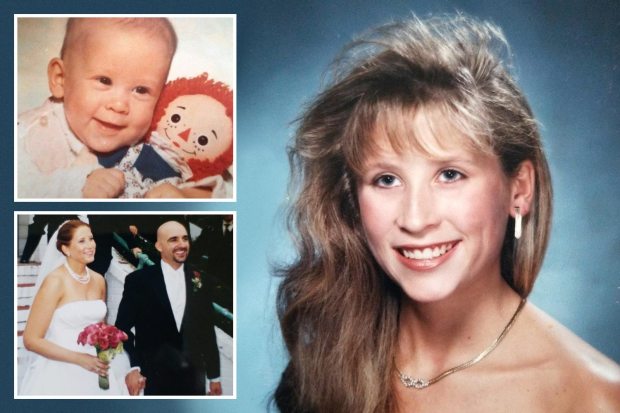

DAWN Covino, 46, had no idea she was born intersex – until a DNA test to find out more about her heritage revealed she had male chromosomes.

Dawn got married to Robert, the couple adopted twins, her dream of being a mum had come true.

When my mum started crying down the phone, I sat in stunned silence. At 38, after decades of feeling like something was wrong with me, I’d finally found the reason why. I was intersex.

I grew up in Long Island, New York, the middle of three daughters. My parents Carol and Thomas weren’t the kind of people who talked about feelings – and definitely not about our bodies.

As a kid I was happy and outgoing, but aged 12 I began to feel out of place. Friends spoke about their periods, but mine hadn’t started yet. Over the next few years I developed breasts, but my period never arrived and I didn’t have any body hair, which I found mortifying.

After gym class, I’d hide in the changing rooms, terrified my friends would notice that I was different. I did my best to hide my body at home, too, but one day in 1989, when I was 15, my mum asked if I had any hair under my arms.

Feeling embarrassed, I said no, and she made me a doctor’s appointment. We didn’t discuss what was going on at all, and when the doctor did an internal exam, I was traumatised. I saw three more doctors in quick succession for more internal exams, blood tests, and scans. No one explained anything, and I didn’t have the confidence to ask any questions.

Instead, I gathered snippets of information from the conversations the doctors would have with my parents. I heard that I’d been born without a uterus and would never get my period or have a baby.

I also heard the word “gonads”, which I assumed was another word for ovaries. It was pre-internet days, so I couldn’t check what the word meant. I was told I’d be having my gonads removed because they were pre cancerous, and went in for surgery a month before my 16th birthday.

When it was over, I was given oestrogen pills to take for the rest of my life, but we never discussed the fact I wouldn’t be able to have children. I did my best to shut the whole thing out, but I felt heartbroken that I’d never be a mum, and began to think no boy would ever want me.

When I did get my first boyfriend later that year, I went on to lose my virginity to him, but I was incredibly cautious about the whole thing. When I went to university in New York to study criminal justice and psychology in 1991, I began to have a lot of casual sex. It made me unhappy, but I wanted to feel validated.

Whenever I registered with a new doctor I’d tell them my medical history – that I was born without a uterus, my ovaries had been removed at 15 and that I was taking daily oestrogen. Every single doctor just accepted what I said.

Dating in my 20s meant deciding when, or if, to tell a guy that I couldn’t have children. Even though men were never put off, it hurt me to talk about it. It reminded me yet again that something was wrong with me. Then, when I was 28, in February 2002, I met Robert, now 46, on holiday with mutual friends.

We hit it off straight away. After five months of dating, I took a deep breath and told him that I couldn’t have biological children. But he took it in his stride, and we got married on August 13, 2004. There were still tough moments, however. When two of my best friends became pregnant at the same time, I struggled with jealousy, which was painful. So, in 2005, Robert and I began to look into adoption.

It was a long process, but in November 2007, we adopted one-year-old twins, a boy and a girl. My dream of being a mum had come true. When the kids were five in 2012, I decided to do DNA tests on them. They both have additional needs, so I wanted to find as much out about their health history as possible. I bought £75 swab tests online, and once I’d put them in the post, I decided to do one on myself too.

My dad, who had died from a heart attack in 2008, had always said his family was from Poland, and I thought it would be great to find out more about my heritage. Two weeks later I got an email from the DNA company, telling me something was wrong with my sample.

I’d written on the forms that I was female, but my sample showed XY chromosomes, which are male. Assuming that there had been a mix-up, I just sent off another sample. But then a doctor from the DNA company called me with some questions. She asked if I’d been born with a

uterus, and if I’d had an operation when I was younger.

That’s when she said that she thought I had CAIS – complete androgen insensitivity syndrome. She explained that it’s when babies are born presenting as female – with external female genitalia – but without ovaries or a uterus. Instead they have internal testes and XY chromosomes. I was overwhelmed, but not by shock or horror. All I felt in that moment was relief – suddenly, everything made sense.

As soon as I put the phone down, I started researching online. I learned intersex is an umbrella term for differences in sex traits or reproductive anatomy. CAIS is one of the conditions that comes under that umbrella, and it affects one in 20,000 people. I called my mum, which is when she burst into tears.

She explained that at the time she found out, doctors believed that you were protecting a child by not telling them, and she’d planned to take the secret to her grave. I could have been angry, but as a mother myself, I understood that my parents had tried to do the best they could. I didn’t tell Robert until I’d visited a geneticist myself a few days later and had the diagnosis confirmed.

I sat down with him over dinner, and nervously said that I had something to tell him. He looked really frightened. When I explained, he froze, then smiled in relief. He thought I was going to tell him I had cancer! The fact that it didn’t alter the way he saw me was amazing.

Eager to discover as much as I could about being intersex, I found InterConnect, an online support group, through which I became friends with others who were intersex.

Most read in Fabulous

Through the group I’ve learned 1.7% of the population is intersex, but so many are scared of the judgement that comes from being open about it. I identify as female, as it’s how I’ve lived my whole life, but I’m not ashamed of the term intersex.

Telling my story is liberating. I want those in a similar situation to know they are not alone. I don’t want other young people to suffer the way I did.

Read More on The Sun

CAIS doesn’t define me – I’m a wife, a mum, a psychologist and friend. But I’m not ashamed of my body or who I am any more.

- For more information, visit

GOT a story? RING The Sun on 0207 782 4104 or WHATSAPP on 07423720250 or EMAIL [email protected]