Undercover cop Neil Woods, who put dealers away for 1,000 years, reveals how mission made him change his mind on the ‘failed’ war on drugs

'Once the evidence shows that what I was doing was wrong, I am duty bound to put myself at risk for doing what is right now,' he says

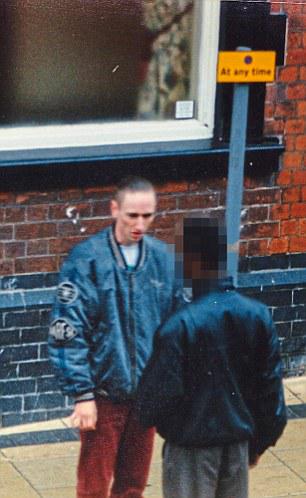

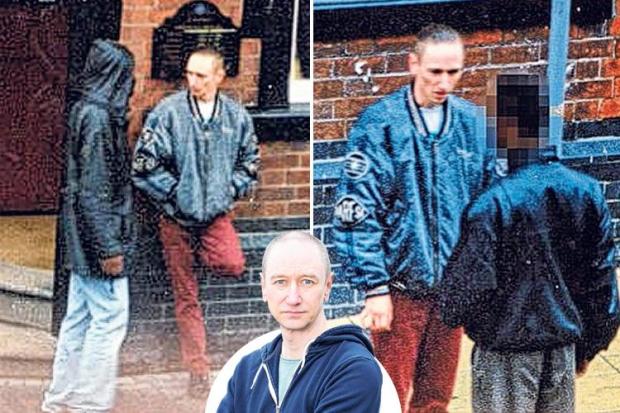

HUNCHED over, hollow-cheeked and dressed in grubby clothes, Neil Woods looked like any rattling junkie scurrying off in search of a fix.

But the father-of-two was actually an elite undercover police operative — posing as a helpless heroin addict to infiltrate violent drugs gangs in the UK.

The father of two would buy drugs off street-level dealers, forging connections to work his way into networks of hardened gangsters.

During a 14-year covert existence Neil was forced to take drugs to keep his cover, and exposed the increasingly barbaric tactics drugs gangs used to enforce silence.

His efforts put away hundreds of criminals for an estimated 1,000 years combined.

The veteran of the war on drugs has now written a book about his life undercover, Good Cop, Bad War.

Neil first joined Derby Police aged 19, but did not find his niche until he went undercover for the drug squad, where he stayed from 1993 to 2007.

He said: “To be honest I enjoyed the intellectual exercise of lying to people and manipulating them.

MOST READ IN NEWS

“It was invigorating to find something I was the best at. I was making it up as I went along.”

Neil, now 47 and retired from the force, would pose as a junkie, arriving in each new city with a fake name and kitted out in distressed charity shop clothes.

By walking fast and bent at the double he was indistinguishable from a “rattling” junkie suffering from stomach cramps while searching for the next score.

He would quickly ingratiate himself with homeless addicts, even helping them to shoplift to curry favour.

These street-level addicts could then introduce him to dealers, who in turn gave hints to the network of gangsters controlling the drug supply in towns and cities across the UK.

Neil said: “I could tune into the street in every city I worked in. Become a part of the homeless people, the addicts.”

Occasionally he would pose as a low-level criminal, but that was fraught with other risks.

In Derby Neil pretended to be an ecstasy dealer as part of sting operation in a pub notorious for its connections to the criminal underworld.

As part of his cover Neil had pretended he was an amphetamine expert who had taken the drug hundreds of times.

One day a gangster, referred to in the book as Alan, slapped a bag of 40 per cent pure speed on the table.

The usual street-level stuff is just five per cent pure.

Neil said: “It was a silly situation — I’d set myself up as a connoisseur of amphetamines and this was given to me as a treat.

“It was supposed to be the strongest stuff I’d ever had — and obviously it was because I had never actually had it before.

“It was a bag of toxic-looking pink sludge. I took a bit of the pink goo on my finger and knocked it back with a slug of beer.

“Alan said: ‘No, no, no — take a f***ing proper hit. It’s on me.’

“There was no option. I took a massive lump and slammed it down. An awful chemical heat rose from my kidneys, followed by an unbearable dryness of the eyeballs.

“My heart started to pound like a pneumatic drill.”

Neil’s fellow undercover operative got him out of the pub as quick as he could without raising suspicions.

Neil said: “I felt anxious and I kept grinding my teeth.

“I drank eight cans of Stella to try and take the edge off — I didn’t even feel the effect of the alcohol. I was up for three days.

“On the plus side my house has never been cleaner and I was able to let my wife sleep through the night while I cared for our baby.”

A few days later a team raided The Lord Stanley to arrest those who Neil had gathered evidence against.

Disappointingly Alan was tipped off about the raid and managed to escape without being arrested.

As police tactics grew more sophisticated, the gangs only responded with more violence and intimidation.

While he had originally worked for Derbyshire’s drugs squad, his success saw him loaned out to other regions across the country.

In Northampton, Neil discovered a shocking new punishment for informants — the gang rape of a girlfriend or sister.

He said: “It was like an arms race. Every time we found new ways to take the gangs on they would increase their violence and intimidation tactics to keep communities living in fear and less likely to talk.”

He stopped the bulk of his undercover work in 2007 but remained with the force and still found himself on the drugs front-line.

Neil’s final operation before leaving the police was in Brighton in 2011 , where he made a chilling discovery.

At the time the city had the highest rate of heroin overdoses in the country, five times the national average.

And when Neil hit the streets he discovered a culture of fear among the homeless population.

Addicts warned him that if the local dealers thought he had talked to police, the next hit of heroin would be adjusted to a lethal dose.

Neil said: “It was pure horror. It was no accident that there were so many heroin overdoses in the city. It was murder by narcotic.

“The gangs knew if they made it look like an accidental overdose the police would never investigate. The addicts lived in constant fear.”

Neil begged senior officers to reopen the accidental death files and stick them back on the books as unsolved murders.

However officers refused. Neil said: “I was laughed at. They seemed to think that a dead junkie was a good junkie — they didn’t care about them.

“That was the moment I flipped, this was not why I joined the police.

“It is hard to see that you’re causing more harm than good but from that moment I knew the war on drugs was doomed.”

Neil left the battle lines the war on drugs as a battle scarred veteran, suffering from PTSD which he spent a year trying to recover from.

He said: “I am still twitchier than I was until 2011. A lot of ex-undercover cops suffer from this.

“My PTSD is sometimes called ‘moral damage’.

“The things which keep me up at night are not the memories of all the times I thought I would die, it was the people I manipulated in pursuit of evidence.

“Lots of poor junkies went to prison because of me. They were generous and helpless people who needed help, who sold drugs to fund their habit, not gangsters but addicts who were sent down on possession or dealing charges.”

Today, Neil believes drugs policy in the UK is failing.

He is now chairman of the UK branch of Law Enforcement Against Prohibition, a pressure group of current and ex-police officers who want to see an end to the war on drugs.

Neil said: “I’m pleased that I was able to put a lot of really vicious people behind bars, but I don’t think my work did anything to damage the drug gangs in the UK.

“I only interrupted the drugs supply in any city I worked in for two hours.

“At the end of every operation there was an increase in violence as thugs attempted to fill a power vacuum.

“People would murder each other over a phone number, knowing that hopeless addicts would keep it ringing off the hook.” He is now considered a whistleblower for his outspoken views on drug crime, and claims his former colleagues have been warned off by senior police from contacting him.

But Neil has no regrets about speaking out.

He said: “I used to put my neck on the line for something I believe in.

“Once the evidence shows that what I was doing was wrong, I am duty bound to put myself at risk for doing what is right now.”

- Good Cop, Bad War by Neil Woods is out in paperback on Thursday. Published by Ebury Press, £7.99.

WHAT NEEDS TO CHANGE... AND WHY

HERE Neil explains how drugs policy should change in the UK – and why.

❶ Heroin should be provided by doctors to addicts and all other drugs should be sold under strictly regulated conditions. I’m not talking about flogging heroin in the corner shop, it would just be available to people who need it. ❷ Legalising drugs will stop corruption in the police force. The drugs trade is worth £7billion, and with that kind of money criminals can afford to have people on the inside. ❸ We need to take the power away from the gangsters. Money is power and they make all their money from drugs. We won’t win until we take the market off them. ❹ Teenagers can get hold of cannabis far easier than alcohol. Dealers don’t want to see photo ID, they want to see a £10 note. Less than one per cent of teens can get hold of alcohol in the UK, which shows we are phenomenal at regulation in this country. By not regulating the drug supply legally as we do with booze, we leave it to gangs, who recruit children directly from the cannabis market. I’ve seen kids grow from misguided teens to hardened gangsters. We need to separate organised crime from our children. ❺ Heroin addicts are often victims, often turning to heroin as a comfort after facing years of sexual or physical abuse. No British citizen should be left behind. ❻ Those who don’t care about addicts should think about their home insurance. In Switzerland when they introduced a programme to distribute heroin legally to addicts, burglaries dropped in half. Shoplifting almost disappeared and they have nearly eliminated street prostitution. All these people were rescued from exploitation and the public benefitted from a drop in crime.