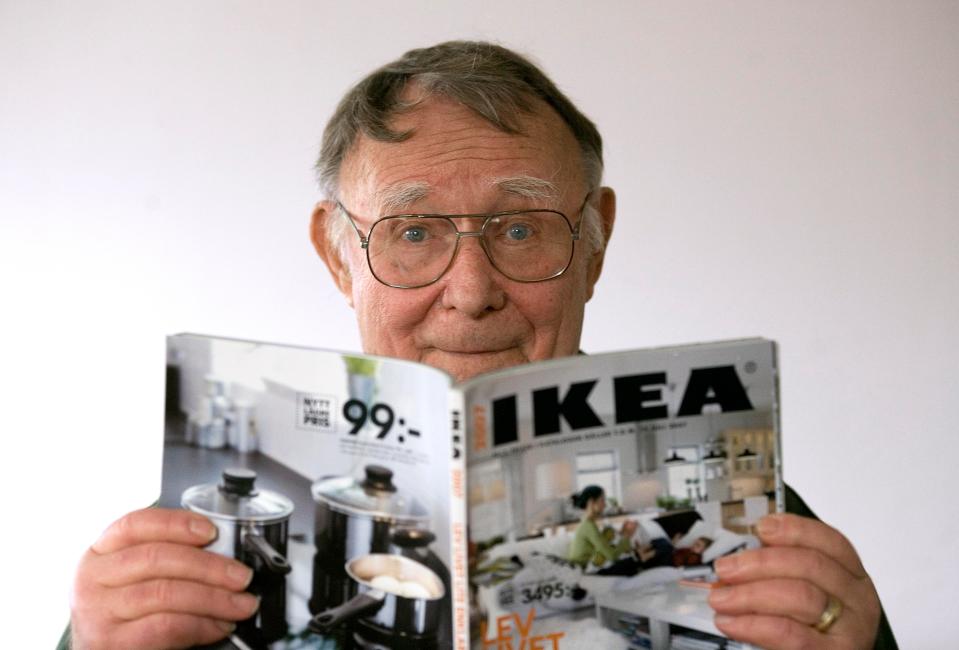

‘Stingy’ Ikea founder Ingvar Kamprad, worth £54billion, was as cheap as his furniture, bought clothes in flea markets and drove a 20-year-old Volvo

Ingvar Kamprad — who died yesterday aged 91 — was 'stingy' and 'disagreeable', despite being one of the richest men in Sweden

YOU may not know his name but chances are you have sat on, slept in or cursed at some of his furniture.

Ikea founder Ingvar Kamprad is the undisputed father of flat-pack and built a £54billion empire based on self-assembly and Scandinavian style.

But despite his estimated fortune, the enigmatic entrepreneur — who died yesterday aged 91 — was “stingy” and “disagreeable”, and criticised for tax avoidance and links to the Nazis.

The Swede flew economy, stayed in cheap hotels, drove a Volvo he had owned for 20 years and wore clothes bought from flea markets.

He had little regard for what people thought of him and was unapologetic, even proud, of his penny-pinching ways.

Ingvar once said: “People say I am cheap, and I don’t mind if they do.

“I could regularly travel first class but having money in abundance doesn’t seem like a good reason to waste it.

“Why should I choose first class, to be offered a glass of champagne from the air hostess? If it helped me arrive at my destination more quickly, then maybe.”

A more questionable example of his frugality was his admission in 2008 that he saved money by getting his hair cut when visiting poor countries.

He told a Swedish newspaper: “Normally I try to get my hair cut when I’m in a developing country. Last time it was in Vietnam.”

Later he tried to explain that it is “in the nature” of people from his home town of Smaland “to be thrifty”.

He added: “We have built the entire business on it.”

Indeed, in 2014 leaked files showed Ikea was engaging in corporate tax avoidance by squirreling away money into offshore tax havens.

But while the pioneer’s stinginess had mostly been a noteworthy quirk, it was his links to the Nazis that dealt a more serious blow to his reputation.

Ingvar’s German grandmother was “a great admirer of Hitler” and, in 1994, it emerged that Ingvar had a close friendship with pro-Nazi politician Per Engdahl in his late-teens and early-twenties.

The leader of the quasi-fascist neo-Swedish movement was even a guest at Ingvar’s wedding to first wife Kerstin Wadling in 1950.

Ingvar later described that time as “the greatest mistake of my life” and even wrote a letter to his employees asking for their forgiveness.

The issue was dragged up again in 2011, after author Elisabeth Asbrink claimed the businessman’s affiliation with fascism went deeper.

Facts and figures

- Average store size is about 300,000 sq ft – as big as 42 tennis courts

- The Billy bookcase sells 500,000 every year – one every five seconds

- Ikea has sold 11.6bn Swedish meatballs and 1.2bn hot dogs in UK

- 180m people read catalogue every year – twice as many as the Bible

The Swedish writer and journalist accused Ingvar of being an active recruiter for a Swedish Nazi group, and said he stayed close to sympathisers well after World War Two.

Ingvar issued another apology blaming youthful “stupidity”. His spokesman added that there were “no Nazi-sympathising thoughts in Ingvar’s head whatsoever”.

Amid all the controversy, there is no doubting the success of “one of the greatest entrepreneurs of the 20th century”.

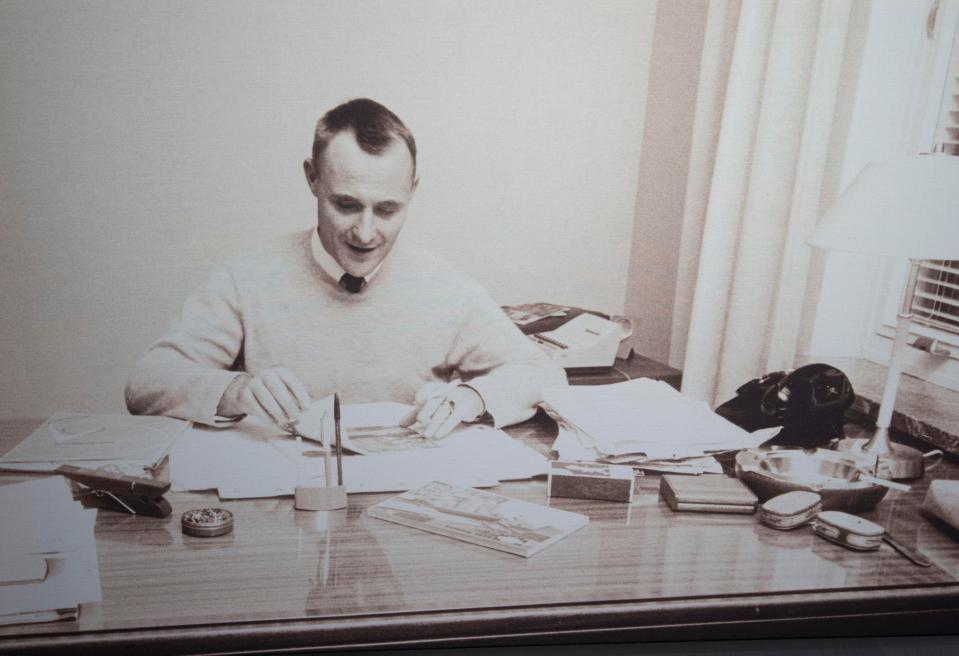

Ingvar was born to parents Feodore and Berta in Smaland, a province in the south of Sweden, in 1929. His dad, a farmer, was a German immigrant.

He got the selling bug early, shifting matches for profit age five. By the time he turned ten he had moved on to Christmas decorations, fish and pencils, which he bought in bulk and sold.

He would deliver to customers in the neighbourhood by bike.

While selling came naturally, he had to work hard at school to compensate for his dyslexia.

Feodore was so impressed by his son’s grades that he gave the 17-year-old a cash reward for all his hard work.

Ingvar knew immediately what he wanted to do with it and launched Ikea, initially a small mail-order business selling items such as pens, wallets, picture frames, table runners, watches, jewellery and nylon stockings.

The name Ikea is an acronym for the initials of his first and last names, plus the initials for the name of the family farm where he was born — Elmtaryd — and the nearest village — Agunnaryd.

As his business grew beyond selling mismatched small items, it was when Ingvar reached 30 that Ikea, as we know it now, was truly born.

His lightbulb moment came as he watched an employee battle to fit a table into the back of a customer’s car and resolved that the only way around it was to take the legs off.

That was it: Flat-pack furniture. Not only would it change the way customers bought furniture it would also cut his business costs enormously by getting them to pick it up from the warehouse where it was made.

His furniture, all given playful or straightforward names such as the Billy bookcase or Stockholm rug, are now sold from more than 400 Ikea stores globally.

The in-store restaurant has become so popular, serving up Swedish classics such as meatballs and mash, that the company has considered opening an independent restaurant chain. The dishes share a quality with the furniture — simplicity.

The flat-pack idea was a revelation but, if anything, was too successful. It helped slash costs to such an extent that the expanding brand faced a boycott from local suppliers under pressure from competitors.

New kind of store for all

IT may not seem like it when we have lost the Allen key for the 27th time in an hour, but we value products we assemble ourselves 63 per cent higher than pre-built goods. This is now known as the Ikea effect.

Putting the items together is not always smooth. An Ikea storage unit was even dubbed “The Divorce Maker” for its 32-page manual and 169 screws.

Although, with a tenth of all furniture in British homes said to have been bought from Ikea, it is not surprising that around one in five children here has been conceived on an Ikea bed.

Similar statistics may have existed in Thailand had Ikea not hired translators to check the product names when it first opened there. Some of the Swedish names translated into terms for sexual acts.

True to Ingvar’s eye for a money-spinning idea, the company perfected a technique called “bulla bulla” where items are piled into bins to create the impression of volume. This means people think that they are inexpensive.

Researchers at University College London also found that the winding route through an Ikea store is there to effectively “trap” customers, meaning they get distracted and spend more.

This was where Ingvar’s tenacity began to show its teeth. He upped sticks and moved his operation from Sweden to Poland, eliciting cries of “traitor” from many in his home country.

Author Malcolm Gladwell wrote about Ingvar in his book David And Goliath: Underdogs, Misfits And The Art Of Battling Giants, saying: “1961. Cold War. Tension. At the height of hostilities between East and West, he decides to move from Sweden to Poland.”

He added it was “like Walmart moving to North Korea”.

But Ingvar did not hesitate, according to Malcolm, as he is “not the kind of person who cares about what his peers think of him” — an attitude that was a key part of his success.

The move to Poland followed the breakdown of his marriage to Kerstin, who he adopted a daughter with. In 1963 he married second wife Margaretha Kamprad-Stennert. They had three sons.

Speaking in 2003, Ingvar, who once claimed that “only those who are asleep make no mistakes”, said of Margaretha, who died in 2011: “She has always had to come second or third in my priorities.

“I’d be away from my bed 200 days out of a year. And she more or less had to give up on her career, she used to be a teacher.

“I think sometime she has been plagued by idleness.”

Back at work, in 1973 Ingvar made the unpopular move of transferring Ikea’s headquarters from Sweden to Copenhagen, Denmark.

Saving money, predictably, motivated the switch, this time to avoid unfavourable business taxes for his growing company.

It was typical of his hunger for success and his ease with being, what Malcolm describes as, “disagreeable”.

After his death yesterday, people paid tribute to Ingvar on social media.

The Swedish Foreign Minister, Margot Wallstrom, tweeted that he had “put Sweden on the world map”.

MOST READ IN WORLD NEWS

Ikea released a statement, saying: “He worked until the very end of his life, staying true to his own motto that most things remain to be done.”

Ingvar once told a reporter: “What else could I do with my age? Grow tomatoes in an allotment behind the house?

“I don’t know how to do anything apart from sell furniture. I am your classic specialised idiot.”