Crack down on petty crime and you’ll cut London’s murder rate — it’s what I did in NY and LA

FORMER US police commissioner Bill Bratton slashed the murder rates in New York and Los Angeles during his time in charge.

Here, he tells London’s police how they can do the same.

London is gripped by the highest toll of violent deaths in decades, with 49 killings so far this year.

At the same time New York’s murder rate has fallen 12 per cent, and that follows a historic low last year. It’s now at about the same level it was in the 1950s.

I believe London can turn it around and there are things we did in New York that you can do to make the UK safer.

The old saying ‘You get what you pay for’ is true and resources are critical.

Police services in Britain have been stretched significantly. The Metropolitan Police has already been reduced by ten per cent and reports say it will be cut by a further 560 officers this year.

Yet in New York in 1994, when crime was at its worst, the city hired an extra 6,000 officers to patrol the streets and subways.

New York City focused on what people saw every day and that was the disorder — what we called the “Broken Windows” policy.

This is a theory that visible signs of vandalism and anti- social behaviour, like broken windows, street drinking, graffiti and fly tipping, create an environment which actively encourages further and more serious crimes. Target the petty crimes aggressively and fewer serious ones will occur.

And I began with the belief that, if properly organised and focused, the police could take responsibility for the prevention of crime rather than just responding to it.

In many respects we were returning to the teachings of my personal hero, Britain’s Sir Robert Peel, in 1829 (when, as Home Secretary, Peel founded London’s Metropolitan Police). One of his founding principles is that the police force exists to “prevent crime and disorder”.

By focusing on only one and not the other — which New York did in the 1970s and 1980s and which Britain continues to do — you are not going to resolve things.

If the disorder is not dealt with, it creates an environment where more significant crime will readily occur.

In the 27 months I was police commissioner under New York Mayor Rudolph Giuliani, overall serious crime in New York declined by 39 per cent.

In the previous three to four years it had gone down by around seven per cent.

One of the most dangerous cities in the world was all of a sudden becoming much safer.

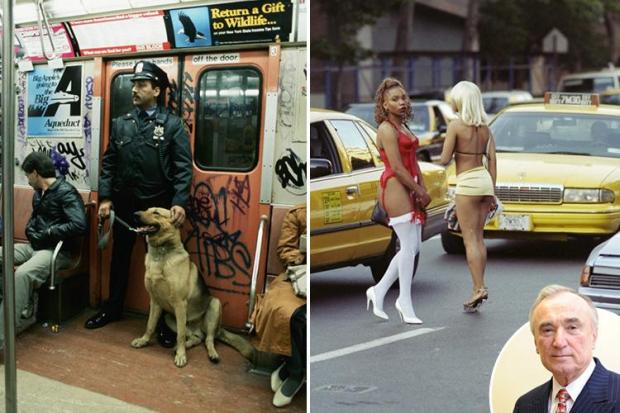

For the first time in 25 years, New York focused on disorder — street prostitution, graffiti, fare evasion on the subways and gangs on the corner.

I came to recognise that all these minor crimes — called “victimless crimes” — did have a victim. That victim was New York City.

So we went after that disorder and it saw results. People who were being stopped and searched were found to have weapons on them.

Criminals were suddenly getting arrested for minor crimes. It made them think twice about going on to commit more serious offences.

The neighbourhoods looked better, so the criminals would think it was being looked after and that they may be arrested.

We also applied more significant use of crime data to identify when and where crime was occurring and who was committing it. It would identify patterns and trends when there were four incidents, instead of 30 or 40. We then very rapidly put cops in those areas.

It’s like a doctor learning how much medicine to apply to a patient’s illnesses. That, plus the focus on disorder, was revolutionary. It appeared that the epidemic of violent crime and social disorder was gone.

Around 250,000 people had been going into the New York subway every day without paying their fares. They were no longer doing that.

On the streets, the prostitutes were disappearing, graffiti was being minimised, the gangs were gone — so the sense of decay and disorder changed very dramatically.

The public could see the results in crime statistics and felt safer because the disorder that had made them fearful was gone. It has helped New York’s tourism and is why the city is so economically viable.

In the 1990s we jailed too many people who could have had drug treatment and alternative sentences.

Now the city’s jail population is down nearly 60 per cent on the 1990s.

I think Met Commissioner Cressida Dick is right when she says social media contributes to the problem. It can increase bullying and terrorism.

MOST READ IN OPINION

But police can also use social media to monitor gangs. There is a bad side and a good side.

London can do something about its rise in serious crime — and if it gets things right, it will become a cycle and things will improve. Just like New York has done.